A street in downtown L.A. will soon be repaved, but the road won’t be quite the standard asphalt road we’re used to. Instead, it will be covered with a material made, in part, from recycled plastic bottles. The plastic is a key in a new process for street paving: For the first time, the city will be able to grind up the existing road and fully recycle it in place, using the plastic to actually make the pavement stronger than it was before.

“New synthetic binders are going to transform the global road construction or road rehabilitation marketplace, and they’re going to allow for roads to be 100% recycled,” says Sean Weaver, president of TechniSoil Industrial, the company that designed the new process. “That’s always been the holy grail of the road construction market—could you recycle 100% of the top surface of the road, grind it up, crush it, and put it right back down, and have that be as durable as the original hot mixed asphalt road?”

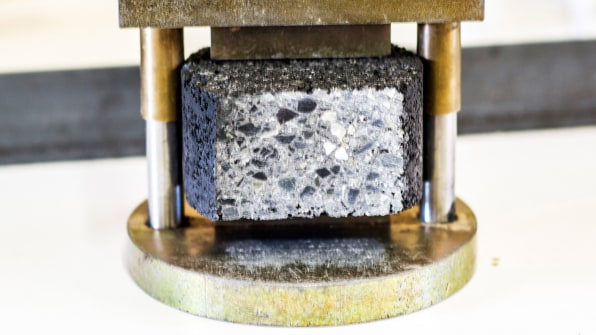

The company has spent the last several years developing the new system, which uses recycled PET plastic, the material used in plastic water bottles, to replace bitumen—a sludge leftover from oil refining that is used to hold asphalt together. The system uses a machine called a “recycling train” that grinds up the top few inches of a street, sends the material into a unit in the back that crushes the asphalt to a specific size, and then mixes it with liquid plastic. “It’s basically one continuous process, where the train mills the road, and then the finished road comes out the back end,” Weaver says.

The basic recycling equipment already existed, but in the past, it was only possible to recycle lower layers of the road and not the top surface, because recycling the material made it lose strength. But the use of plastic makes the road even stronger than it was initially. In lab tests, the company has calculated that its roads can last eight to 13 times longer than a standard road.

The process is also better for the environment, since it reuses materials. If you look at the total carbon footprint of making a road, Weaver says, there’s a 90% reduction in emissions if you recycle it this way instead of repaving the usual way, because of the reuse of materials and the fact that the process can happen at ambient temperatures and also eliminate a lot of driving. “With a traditional road, for every one lane mile, you have to mill out 42 trucks’ worth of waste and haul that away, and bring in 42 new trucks of new hot mixed asphalt,” he says. “We’ve eliminated that 84 trucks of hauling in and hauling out.” It’s also a way to make use of an abundance of plastic waste. “We have a massive amount of polyethylene plastic out there that we have no idea what to do with now that China is not taking it, and we have an end use for it.” While a U.K.-based company is also beginning to use recycled plastic as a binder in newly paved roads, TechniSoil’s process is unique in that it also recycles the asphalt itself.

In some cases, it could cost less than traditional road paving, and because the road will also last longer, cities will save even more money over the long-term. After the city of L.A. tests the material on two sections of roadway this December—a pilot that will take a year or two of study—it may expand to using the process on heavily traveled roads throughout the area, including truck-filled streets leading from the Port of Los Angeles. TechniSoil, which has tested the process in all climates, also plans to expand to other cities.

Comments